Over the past decade, neuroscientists at the Duke University Center for Neuroengineering (DUCN) have developed the field of brain-machine interface (BMI) into one of the most exciting—and promising—areas of basic and applied research in modern neuroscience. By creating a way to link living brain tissue to a variety of artificial tools, BMIs have made it possible for non-human primates to use the electrical activity produced by hundreds of neurons, located in multiple regions of their brains, to directly control the movements of a variety of robotic devices, including prosthetic arms and legs.

As a result, BMI research raises the hope that in the not-too-distant future, patients suffering from a variety of neurological disorders that lead to devastating levels of paralysis may be able to recover their mobility by harnessing their own brain impulses to directly control sophisticated neuroprostheses.

The Walk Again Project, an international consortium of leading research centers around the world represents a new paradigm for scientific collaboration among the world’s academic institutions, bringing together a global network of scientific and technological experts, distributed among all the continents, to achieve a key humanitarian goal.

The project’s central goal is to develop and implement the first BMI capable of restoring full mobility to patients suffering from a severe degree of paralysis. This lofty goal will be achieved by building a neuroprosthetic device that uses a BMI as its core, allowing the patients to capture and use their own voluntary brain activity to control the movements of a full-body prosthetic device. This “wearable robot,” also known as an “exoskeleton,” will be designed to sustain and carry the patient’s body according to his or her mental will.

In addition to proposing to develop new technologies that aim at improving the quality of life of millions of people worldwide, the Walk Again Project also innovates by creating a complete new paradigm for global scientific collaboration among leading academic institutions worldwide. According to this model, a worldwide network of leading scientific and technological experts, distributed among all the continents, come together to participate in a major, non-profit effort to make a fellow human being walk again, based on their collective expertise. These world renowned scholars will contribute key intellectual assets as well as provide a base for continued fundraising capitalization of the project, setting clear goals to establish fundamental advances toward restoring full mobility for patients in need.

Walk again Project Homepage

Quickly grabbing a cup of coffee is an everyday action for most of us. For people with severe paralysis however, this task is unfeasible - yet not "unthinkable". Because of this, interfaces between the brain and a computer can in principle detect these "thoughts" and transform them into steering commands. Scientists from Freiburg now have found a way to distinguish between different types of grasping on the basis of the accompanying brain activity.

In the current issue of the journal "NeuroImage", Tobias Pistohl and colleagues from the Bernstein Center Freiburg and the University Medical Centre describe how they succeeded in differentiating the brain activity associated with a precise grip and a grip of the whole hand. Ultimately, the scientists aim to develop a neuroprosthesis: a device that receives commands directly from the brain, and which can be used by paralysed people to control the arm of a robot - or even their own limbs.

One big problem about arm movements had been so far unresolved. In our daily lives, it is important to handle different objects in different ways, for example a feather and a brick. The researchers from Freiburg now found aspects in the brain's activity that distinguish a precise grip from one with the whole hand.

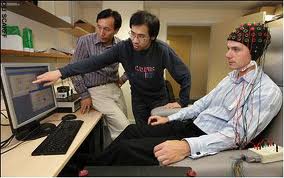

To this end, Pistohl and his collaborators made use of signals that are measured on the surface of the brain. The big advantage of this approach is that no electrodes have to be implanted directly into this delicate organ. At the same time, the obtained signals are much more precise than those that can be measured on the skull's surface.

The scientists conducted a simple experiment with patients that were not paralysed, but had electrodes implanted into their skull for medical reasons. The task was to grab a cup, either with a precise grip formed by the thumb and the index finger, or with their whole hand. At the same time, a computer recorded the electrical changes at the electrodes. And in fact, the scientists were able to find signals in the brain's activity that differed, depending on the type of grasp. A computer was able to attribute these signals to the different hand positions with great reliability. Now, the next challenge will be to identify these kinds of signals in paralysed patients as well - with the aim of eventually putting a more independent life back within their reach.

Source Bernstein Center Freiburg

In the current issue of the journal "NeuroImage", Tobias Pistohl and colleagues from the Bernstein Center Freiburg and the University Medical Centre describe how they succeeded in differentiating the brain activity associated with a precise grip and a grip of the whole hand. Ultimately, the scientists aim to develop a neuroprosthesis: a device that receives commands directly from the brain, and which can be used by paralysed people to control the arm of a robot - or even their own limbs.

One big problem about arm movements had been so far unresolved. In our daily lives, it is important to handle different objects in different ways, for example a feather and a brick. The researchers from Freiburg now found aspects in the brain's activity that distinguish a precise grip from one with the whole hand.

To this end, Pistohl and his collaborators made use of signals that are measured on the surface of the brain. The big advantage of this approach is that no electrodes have to be implanted directly into this delicate organ. At the same time, the obtained signals are much more precise than those that can be measured on the skull's surface.

The scientists conducted a simple experiment with patients that were not paralysed, but had electrodes implanted into their skull for medical reasons. The task was to grab a cup, either with a precise grip formed by the thumb and the index finger, or with their whole hand. At the same time, a computer recorded the electrical changes at the electrodes. And in fact, the scientists were able to find signals in the brain's activity that differed, depending on the type of grasp. A computer was able to attribute these signals to the different hand positions with great reliability. Now, the next challenge will be to identify these kinds of signals in paralysed patients as well - with the aim of eventually putting a more independent life back within their reach.

Source Bernstein Center Freiburg